Page

9: Aklavik

Reindeer

Herds

One

thing different about Aklavik was an interesting addition to our customary

northern cuisine. Venison was occasionally available, not from deer,

but in the form of reindeer meat. This delicacy was available after

the Reindeer Station's annual cull of the government herds north of

Aklavik. The last time I had eaten venison was during the war, when

Dick was stationed at Arundel in Sussex. The Duke of Norfolk's deer

herd roamed the park surrounding his family seat, Arundel Castle,

and was regularly culled. Since there was not enough for the meat

to be officially rationed, it could be purchased without sacrificing

food ration coupons, and made a useful addition to our wartime diet.

The

Mackenzie delta's original herd of three thousand reindeer was imported

from Alaska. It took six years, from 1929 to 1935, for them to accomplish

the journey to the 6,600-square-mile reindeer reserve on the east

side of the Mackenzie River, about fifty miles from Aklavik. The government

hoped that the herd would provide not only a source of food for the

natives but also a means of employment. Laplanders were brought over

from Norway to train Inuit who wished to become herders. In 1951 the

first herd had become three, comprising 5,600 animals, tended by about

twenty-five Inuit and a few Laplander herders, the latter descendants

of the original Laplanders who had trained the first Inuit herders.

The residential school took a class of ten or so Inuit boys to the

yearly roundup in July so that they could see the work involved and

perhaps become herders themselves. After this annual roundup venison

would be on sale in the Hudson's Bay Company store in Aklavik, and

it made a pleasant change in our diet. It was a very lean meat and

needed careful cooking, but was quite delicious.

There

is almost no physical difference between the reindeer and the caribou.

This created an unsolvable problem when, in January 1949, a Native

was tried for illegal possession of reindeer meat, knowing it to be

such, and selling it as caribou meat. The Aklavik contributor to Notes

of Interest reported on the trial, which was naturally of great interest

to the people of the delta. After various witnesses for and against

had contradicted themselves, the government mammalogist demonstrated

that the only way to distinguish between the two species was by precise

measurement of the distance between the rows of teeth. Consequently,

the accused was acquitted, and a general warning was issued to hunters

to be careful what they shot - and presumably to try to avoid the

reindeer reserve when hunting for game.

Jill with friends

Fun

and Games

The

children enjoyed having more friends to play with. During the winter,

when it was difficult to play outside, they invented games to play

indoors. One such game, inspired by their earlier trip outside to

visit Grandma in Ottawa, was to pretend that their small tricycles

were cars. The floor plan of the house was suitable for this game,

as it was possible to ride in a circle right around the ground floor,

through the kitchen, hall, and living room, as many times as they

wanted. One bright idea was to pretend they were getting gas for their

cars. The gas pump was the large soda-acid fire extinguisher in the

hall, and they duly attached its hose nozzle to the back of one of

the cars. Unfortunately, they forgot to remove it when they drove

off. The extinguisher fell over and immediately began to gush clouds

of foam. There was no way possible of turning it off once the chemical

reaction had begun. An urgent call for help brought Dick, who with

some effort managed to detach the inextinguishable extinguisher from

the tricycle and rush out of the house with it, still spraying and

spewing like mad. A couple of passers-by were intrigued - people usually

rush into a house with a fire extinguisher! In spite of much washing

and scrubbing I never did get the stains completely off the hall walls;

I resorted to hoping that it would be repainted in time for the next

occupants.

Permafrost

Some

things were very different indeed in Aklavik, particularly one that

was to affect the future of the town: the peculiarity of the soil

on which Aklavik was built. It was frozen solid, except for two months

in the summer, when it melted to a depth of six inches or so. As the

permafrost - the moisture in the soil - froze and melted in succeeding

cold and warm seasons, the surface of the earth would heave, and the

floors of the houses could not help but move up and down in sympathy.

Big jacks were installed in our basement; they were used to raise

or lower the joists above, helping us to cope with the problem of

uneven floorboards.

On

their regular visits, the Royal Canadian Corps of Engineers (RCCE)

inspectors used a simple but effective technique to test whether the

floors of the army buildings were level. They put a table-tennis ball

on the floor and watched which way it rolled. They could then decide

whether the jacks in the basement needed to be wound up or down to

level the floor. Eventually, after judicious winding, the ball did

become stationary. By the time the engineers next visited, the whole

process would invariably have to be repeated.

Another

addition to our basement furnishings was a sump pump. This was useful

when it was necessary to get rid of water seeping into the basement

from the melting permafrost.

These

perennial problems with the silt on which Aklavik was built led eventually

to its being replaced as the local centre of government. In the new

town of Inuvik, on the eastern side of the delta, it was possible

to compensate for the difficulties of permafrost. Inuvik's gain was

Aklavik's loss: the town now has a much smaller population, of only

about seven hundred.

All

Saints Cathedral, "The Cathedral of the Arctic," Aklavik.

All

Saints Cathedral, interior.

All Saints Cathedral

An

architectural highlight of Aklavik in 1952 was All Saints Cathedral,

the Anglican "Cathedral of the Arctic." Built in 1939 to

replace the original 1919 building, it resembled a typical English

parish church. The interior contained a remarkable number of church

furnishings that had been sent from England as gifts. Many had some

historic value as well as being objects of beauty in themselves.

Epiphany

of the Snows, altarpiece in All Saints Cathedral.

Above

the altar hung a painting, Epiphany of the Snows, which seemed extremely

appropriate for a church in the far North. It was a nativity scene

painted by Violet Teague, an Australian artist. The Madonna, in a

long Inuit-style ermine parka and mukluks, holds the baby Jesus, in

ermine parka, pants, and mukluks, on her lap. Bringing gifts to the

Child are, not middle Eastern magi and shepherds, but northerners.

On the left, a Nascopie-Cree from the Ungava Peninsula presents a

live beaver, a Hudson's Bay Company factor offers white fox pelts,

and a Royal Canadian Mounted policeman in dark furs represents protection.

An Inuit in a caribou-skin parka, bearskin trousers, and sealskin

boots offers two walrus tusks, and behind him stands an Inuit woman

from Baffin Island, with a baby in the hood of her caribou-skin parka,

her gift not visible. Two sled dogs, a malamute and a husky, and two

reindeer are present instead of the usual sheep, cattle, or camels.

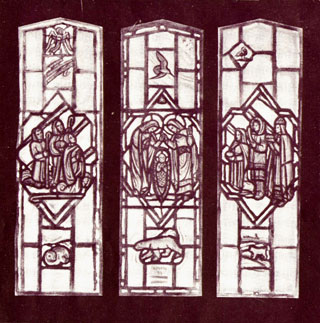

Baptistery

windows, All Saints Cathedral.

The

three colourful stained glass windows in the baptistery were donated

by Inuit members of the congregation. The left one, with a seal in

its lower portion, was given by Susie Wolkie in memory of her husband,

Fred. The middle window, given by Fred Carpenter in memory of his

wife, Lucy, shows a polar bear, and the one on the right, donated

by Charlie Smith in memory of his wife, Lily Sarniak, pictures the

three wise men, one dressed as an Inuit, with a sled dog below.

During our time in Aklavik, Canon Colin Montgomery, brother of Field

Marshal Bernard ("Monty") Montgomery, was the priest responsible

for the Anglican mission and the Cathedral. It is sad to say that

this church, with its fascinating display of adapted and adopted northern

elements, was destroyed by fire in 1972. I do not know whether any

of the contents survived its destruction.

Posting

Our

posting to Aklavik was a completely new experience. Living in the

real land of the midnight sun was wonderful. Unfortunately, our stay

there did not last very long. In January of 1953, six months after

our arrival, Dick was promoted and posted. In keeping with the army's

gypsy way of life, we were soon on our way.

This

time it was south to "fresh fields and pastures new," to

what was to be a new experience, for me although not for Dick: life

in an army camp. Camp Shilo, on the prairies of Manitoba, would reveal

yet another aspect of Canada - although not quite as different from

"ordinary" life as our unique and fascinating northern postings

had been.

Camp

Shilo, Manitoba, 1953: Ian, Jean, Chris, and Jill.

[Next

Page]

Pages: [1]

[2] [3]

[4] [5]

[6] [7]

[8] [9] [10]

[11] [12]

[13] [14]

[15] [16]

Return to top of

page

Return to the Watts

Family page