Page 5: Ft. Providence (continued)

Fort

Providence: Tea dance, July 17-19, 1949

Treaty

Day

Treaty Day each year was a big occasion; that was when the Treaty

Indians who lived outside the settlement gathered in Fort Providence

to receive their annual government payments from the chief magistrate

of the district. According to the station's monthly report in Notes

of Interest, thirty-four tents were pitched by the visitors in June

1951. Our visitors seemed to have a very good time as they enjoyed

their get-together and celebrated the occasion with a "tea dance."

Dr. Truesdell was the chief magistrate of our area and he arrived

for the ceremonies accompanied by a medical team to provide any needed

services, including X-rays.

Treaty day was also a convenient time for Native trappers to seize

the opportunity to complain about the number of beaver that hunting

regulations allowed them to trap in a season. The radio station was

very handy for anyone who wished to send irate messages to the authorities,

such as their Member of Parliament or, as one complainer addressed

his message, to Prime Minister Mackenzie River King.

"The Daily Round, the Common Task"

Cooking provided a challenge or two. We had to ration our year's supplies

carefully so that they would last out the full year before the next

delivery was made, and at the same time we tried to compensate for

the almost complete lack of fresh produce. We had to use our ingenuity,

which was an interesting exercise. I also found myself quite enjoying

baking bread a couple of times a week. The children had fun forming

the dough into different shapes for buns, airplanes being one of their

favourite models.

Our kitchen stove was an clever contraption, basically an oil-stove

with a small electric fan attachment blowing its tiny flame up to

a respectable height and heat. It was an excellent stove with a high

back that had a very convenient shelf on which one could put bread

to rise. If water was kept simmering on the stove underneath, the

bread turned out delightfully light.

For most of the year, looking after the children and the house, cooking,

mending, and sewing, plus baking bread, kept me too busy to be bored.

In the winter, though, one did tend to feel "cabined, cribbed,

confined" and I could understand why symptoms of cabin fever

sometimes developed in the settlement during this season, and why

feuds would occasionally ensue between people. On our neutral territory,

though, it was rather an annoyance when someone walked out of the

house in a huff because the other party in the feud had arrived.

Meeting

the mail plane: Ann Schoales talks to one of the radio operators while

her husband, Frank Schoales, the Hudson's Bay manager and local postmaster,

collects the mail from inside the plane.

The

Mail Plane

The arrival of the mail plane was always an exciting event for the

settlement. Normally scheduled to arrive twice a month, the big Dakotas

were unable to land during the six weeks each of winter freeze-up

and spring thaw. During these periods the mail would usually arrive

in a smaller Norseman plane, but only if conditions were suitable

for landing. At times neither the airstrip nor the river would be

suitable for a plane to land on, whether it was on wheels, skis, or

floats.

The Hudson's Bay trading post manager was also the postmaster and

was responsible for estimating the condition of the airstrip, which

he would check before the time the plane was expected. When the radio

station informed him of its expected time of arrival, he would, if

conditions were suitable, give his permission for the plane to land.

He would then rush out to the airstrip in his truck to collect the

mail, usually accompanied by the radio station truck and anyone else

who wanted a bit of excitement.

After a delay at the HBC post, for sorting, we would get huge sacks

full of newspapers, magazines, and letters, and perhaps a parcel from

Eaton's. We subscribed to the Ottawa Citizen, the London Sunday Times,

Woman's Journal, and Life. It was always fascinating to find out what

had been going on "outside" during the previous month or

two and to catch up with news from home.

Weather

The sky was usually clear except on very cold winter days, when the

smoke from the chimneys of the settlement hung in a low haze just

above the roofs of the dwellings. The stars, whose twinkling was undiluted

by city street lighting, shone very brightly in the cold, clear nights,

and the northern lights were spectacular and wonderful to watch. Sundogs

- a prismatic effect causing spectacular "mini-suns" on

a halo around the sun - made a fascinating addition to winter's special

effects.

I had once read a story set in Alaska that described how words spoken

outside on a very cold day would freeze. On one extremely cold winter

day, the mercury in the official thermometer dropped below the lowest

temperature marked on it. This provided an excellent opportunity to

check the facts of the story, so I asked Dick to say a few words on

his way back to the station after lunch. With great interest I watched

from the kitchen window as he paused several times on his way along

the boardwalk to speak. Each time, the vapour from his breath froze

and hung in the air where he had stopped, leaving a trail of little

clouds along his route to the station. It was fascinating to discover

the possible origin of this story.

Temperatures recorded during the year ranged from a high of 92ºF

(34ºC) in June to a low of -57ºF (-49.4ºC) in December.

For much of the winter it was too cold to snow, and although the snow

had to be shovelled to keep the boardwalks clear, this was no more

work than in many cities farther south. In the spring, when the temperature

reached zero (32º Fahrenheit) and the sun shone brightly, it

felt amazingly warm in contrast to the colder winter weather. "The

boys" would seize the opportunity to take off their shirts and

sunbathe outside the station.

Usually the only sound to be heard in the settlement in winter was

the melodious howling of the tied-up dogs, or the crack of a whip

and the sound of harness bells as a dog team trotted along pulling

a sled. On summer nights the loud hum of mosquitoes outside the screened

windows seemed fierce and menacing. These pests made it impossible

to enjoy a summer picnic without a smudge fire to sit around and a

generous covering of mosquito repellent. No-see-ums and biting flies

joined this hungry horde. If the children played outside, it was imperative

to make sure that they were suitably dressed and their faces and hands

protected by repellent.

Signals station with weather screen at right

Signals

Duties

The North is the cradle of the weather systems of Canada and the United

States, and meteorological data from this area is vital for long-range

weather forecasting. Weather reports were therefore an extremely important

part of the duties of the Signals station staff.

Every hour, day and night, the operator on duty checked the thermometers

inside the "weather screen" outside the station and recorded

the temperatures. The wind speed and direction were checked inside

the station, by means of an anemometer connected to a wind-vane on

the station roof, and the station's seismograph readings were also

noted. The height of the cloud cover was estimated visually, sometimes

by shining a searchlight at the sky. The barometric pressure and amounts

of rain or snowfall were also recorded. Further weather information

was obtained by inflating a weather balloon and sending it soaring

into the air. The children were very impressed by the balloon launches.

Occasionally, as a special treat, they would be given one of the big

red balloons to play with.

At the end of each week, and of each month, summaries of all these

reports were compiled and sent to Headquarters in Edmonton. When the

station staff were reduced by two in October 1950, the hourly weather

reports became one synoptic version every six hours, with hourly reports

provided only upon request. The staff reduction was made necessary

by a shortage of radio operators. During this period, they were more

desperately needed overseas with the Canadian troops who were taking

part in the Korean War.

Weather information was also vital for the pilots of the planes that

landed, took off, or flew over Fort Providence, whether they flew

bushplanes, commercial airliners, or military aircraft. An essential

part of the station's duties was supplying this information to the

planes, keeping track of their flights, and notifying their destinations.

Riverboats also needed to send and receive messages, usually about

their progress along the river. The operators also transmitted and

received messages from and to the inhabitants of Fort Providence.

Less frequent customers were oil companies drilling in the neighbourhood.

We were all intrigued when one exploration team arrived in a helicopter;

we were used to seeing airplanes only, varied as they were by their

landing gear - wheels, floats, or skis.

The station's duties also included providing the settlement with its

minimal local telephone system, which served, on a party line, the

RCMP, the HBC post, the single and married quarters, and, of course,

the station itself. A line to the Roman Catholic mission was added

in 1951. Subscribers were asked not to pick up the phone when it rang

four times, as this was the RCMP's number - curiosity as to what crime

might be in progress had to be satisfied at some later date!

The road to the airstrip, spring repairs: Bill Aird (RCASC), Dick

Watts (RCCS),

Art Fieldsend (RCMP), and Frank Schoales (HBC).

Another

chore, shared by other inhabitants of Fort Providence, was that of

keeping the road to the airstrip in good enough condition to enable

the two vehicles of the settlement - the Signals and Hudson's Bay

Company trucks - to meet the planes when they arrived.

Radio station (left) and engine house (right)

Engines

The names of the engines - "Lister" and "Waukesha"

- were not words that one was eager to hear. Their mention usually

indicated some depressing mechanical problem. It was indeed very rarely

that the monthly report did not include the melancholy "trouble

with engines." The staff expended much time and effort maintaining

these engines, which were absolutely essential for the station, as

they enabled the generators to produce power, light, and heat for

the buildings in the compound.

Most important of all the station's needs, at least to the powers-that-be

in HQ, was sufficient power to keep the station on the air. Even regular

overhauls failed to prevent the many problems that occurred as one

part of the engines after another needed repair or replacement. If

an urgent replacement was needed, it had to be flown to the station

from "outside." The station mechanic/operator and his assistants,

the rest of the boys at the station, needed patience and perseverance.

The cook and I did our best to sympathize and provide what we hoped

was comfort and support in the way of refreshment and encouragement.

Electrical power was the lifeblood of the compound. The station was

on the air for twenty-four hours a day, which was difficult to achieve

when it was short-staffed. The staff were working extra shifts when

an eagerly-awaited replacement mechanic/operator arrived in March

1950. On the way to the station from the airstrip, he was asked if

he knew Morse. He replied, "No, who's he?" He left Fort

Providence in June, never having learned how to send and receive in

code - the usual troubles with the engines had kept him much too busy!

Mail

and Messages

Office procedures took on a hectic pace when the twice-monthly mail

plane arrived on its flight north, as it always brought mail from

HQ in Edmonton. This had to be answered at once so that replies could

be included in the mail going out on the return flight two days later.

It made for a very busy weekend for whoever was in charge of the station.

Non-mail communications from Edmonton were sent and received in Morse

code, as were all other messages. When they were on duty, the more

experienced radio operators preferred to use a "bug" when

transmitting. This was a faster, more sensitive, but more difficult

to use, version of the Morse key. Instead of moving up and down, the

bug's key was moved from side to side, unlike the standard army-issue

key, so familiar from movies in which the valiant operator sends an

SOS as his ship sinks or, in war movies, a "V for victory"

signal. I think that these two messages must be the only Morse code

recognizable to the general public - perhaps permanent memorials to

this past era.

The uninitiated were impressed to discover that an operator could

read and understand the dots and dashes coming from the radio set

as easily as if he were reading a book. When Dick was at work in his

office on a mail weekend, he could compose a letter to HQ on his typewriter,

answer a question from someone in the station, and chuckle at a joke

being transmitted in Morse code from another station - all at the

same time!

Love

and Marriage

After the end of the war, a soldier was no longer required to obtain

his commanding officer's permission before he could marry. However,

the army authorities seemed reluctant to allow total freedom of choice.

They were not in favour of intermarriage between the signalmen and

the local women. I am not sure whether this was from some paternalistic

feeling of responsibility towards the young and inexperienced soldiers

or a relic of the earlier marriage regulations. Perhaps it was because

of the difficulties of posting a man married to a Native northerner

to other parts of Canada.

Whatever the reason for this concern, one result was that whoever

was in charge of a northern station had to keep track of the love

life of his staff and decide if their intentions were both honourable

and serious. If he decided that they were, he had to keep HQ informed.

This was hardly an easy matter to determine and caused many a headache

for the unfortunate who had to do it. To add to his troubles, all

personal information had to be transmitted in a confidential code,

thus adding extra coding and decoding time and labour to an unpleasant

duty.

RCMP

compound, 1949

RCMP

Constable Art Fieldsend. - 1948

Law

and Order

Whoever was in charge of a station was sometimes required to act as

the local Justice of the Peace. This office devolved upon Dick, and

he was duly appointed a magistrate "with the powers of one,"

which seemed to mean that he had no power to perform a marriage ceremony.

His duties were not overwhelming, as there did not appear to be an

enormous amount of crime in Fort Providence, apart from illegal trapping

and some local parties involving too much homebrew and subsequent

fights.

The local RCMP duly informed Dick of the details of any cases coming

up for judgement. In court he listened with conscientious patience

to the constables' accounts and to those of the accused, sometimes

through an interpreter, who translated, if necessary, from Slavey.

After one prisoner gave a long and impassioned speech in Slavey, Dick

was a little surprised to hear the translation - "Not guilty"!

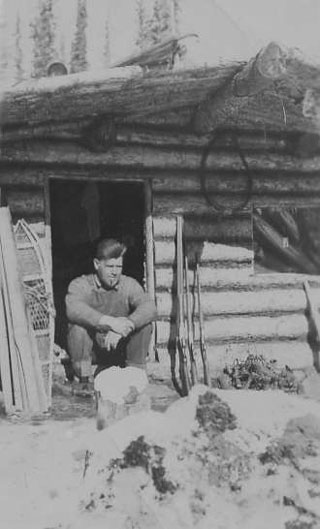

Sandy Davidson at one of his trapline cabins

The

White Trapper

Sandy Davidson, the one white trapper in the settlement, lived just

outside our compound fence, facing the main road. His devoted team

lived in their own doghouses behind his cabin.

L

to R: PMQ, oil tank, single quarters, and Sandy Davidson's cabin.

The doghouses are to the left of his house, level with the oil tank.

Sandy

leaves for his trap lines

Every

year during the summer, Sandy took supplies to his winter cabins by

plane. In the latter part of August or early September he left Fort

Providence for his traplines, near the Horn Mountains. He travelled

by canoe, and his dogs either rode with him or ran along the riverbank

beside the boat. On their routine patrols during the winter, the RCMP

constables would check on him regularly and bring back news of how

he was getting on and how good or bad the trapping was that year.

Each spring or early summer he would return from his traplines with

a load of wonderful furs. After his winter alone except for his dogs,

he would spend an entire weekend recovering from the isolation by

talking nonstop to the Signals staff on duty. As the shifts changed

every eight hours during the forty-eight hours of the weekend, he

would carry on with his recital to whichever operator was on duty,

making up for his long winter's silence. His tales of winter adventures

and the different animals he had encountered were fascinating. He

would talk about his dogs as if they were fellow adventurers, specially

his lead dog, Charley.

Jimmy

Carter (RCMP), Hank Hoiland, Sandy Davidson,

and Joe Funfer in front of Sandy's cabin.

In the summer Sandy occupied himself with making homebrew, hiding

the bottles under the floorboards of his cabin when he saw either

of the two RCMP constables approaching along the road. The boys at

the radio station had a standing invitation to join him for a "cool

one." When Dick, Jill, and I paid him our first visit, Sandy

immediately offered us a beer. Before I realized it, he had included

Jill, giving her some in the cap of a whiskey bottle - she loved it!

We finally managed to convince him that it was not an appropriate

drink for one so young; she had to wait a good few years before she

was able to repeat that first experience.

Jean,

Jill, and Curly Folkins, burning the Christmas tree

Curly

Folkins

There are quite a few northern names that I cannot easily recall,

but there is one that I will never forget - Curly Folkins.

The fence that surrounded the Signals compound enclosed only the back

of our house. The other three sides of the house were open to the

surrounding bush. To enable our little girl, Jill, to play outside

safely, we fenced in some land in front of the house. This also enabled

us to make a garden in which we managed to grow lettuces and a few

flowers during the long, sunny days of summer. The wire fence, which

we had thought impossible for a toddler to get through, unfortunately

proved to be not impossible at all for Jill. One horrible morning

after letting her out to play, I looked outside to see no little girl

in the garden.

This was the time of year when the ice was breaking up on the river.

I rushed over to the station, and Dick and the boys immediately dispersed

to look for her. It was Curly Folkins who found Jill - just as she

was about to step onto the broken-up ice of the river. She was in

pursuit of a puppy that must have wriggled its way into our yard through

one of the squares of the wire fence. She had then followed it as

it squeezed its way out again.

Northern rivers and lakes can be a dreadful danger for children. During

our posting to Aklavik, two children were drowned in the Mackenzie

when they fell into a hole in the ice where people had been cutting

ice to melt for water. I can never thank Curly enough for finding

Gillian and saving her from a similar fate. This whole incident probably

lasted no more than an hour, but at the time it felt like an eternity.

Recreation and the Social Whirl

We almost invariably provided our own entertainment and recreation.

The men indulged in such sports as fishing (from the shore and from

boats), shooting (ducks, geese, and prairie chicken) in season, exercising

dog teams, sunbathing, and swimming in the river during the short

summer season. Card games were always in fashion, and exchanging visits

with the current Hudson's Bay family and the RCMP constables was an

ever-present way to pass the time pleasantly.

It was always a pleasure when the local HBC post manager had a wife

and family, as it meant that female company was available and there

were other children for mine to play with. Two families were posted

to Fort Providence during our time, with one or two single managers

sandwiched between them for a fairly short period. Both the Schoales

and Hunt families were great company and good friends, and goldmines

of valuable northern expertise.

Spring

"picnic" with the Schoales family - Jean and

Jill, Veryl, Anne, Lynda, and Frank Schoales

Throughout the year, visits and invitations to meals were exchanged

between the single quarters, married quarters, the RCMP post, and

the Hudson's Bay trading post. Although the mission staff kept pretty

much to themselves, we occasionally took the children to visit the

sisters at the mission school. The Christmas season was an occasion

for gathering together by the white population, and on New Year's

Day the Mission staff and the Natives would make ceremonial visits.

Christmas

1951: Front row: Lynn, Ken, and Peggy Hunt

(HBC);

Jean, Jill, Dick, and Chris Watts

Back row: Norm Hambley, Pat Paterson, Curley Folkins,

Bert Rupple, Tommy Scott

The two resident families much appreciated the trouble that the single

quarters "boys" took in 1951 to provide a decorated Christmas

tree (cut from the bush) and Christmas gifts for the children. To

do this required thinking ahead - sending a mail order outside in

time for the parcels to arrive by air before the festive day. It was

very kind and thoughtful of them.

During our time in Fort Providence, the occasional square dance was

held at the single quarters, as it was, apart from the Mission, the

only building large enough to hold a gathering. The dances were highly

successful and the Natives, both men and women, were very energetic

dancers. Angus McLeod, the Native clerk at the HBC trading post, was

an experienced and effective caller. A good time was enjoyed by all.

There was a general election in 1949, and some excitement was aroused

by the separate visits of two candidates. Accompanied by their small

entourages and some bottles of good cheer, they stayed for a few hours

in Fort Providence and then departed in the bushplanes in which they

had arrived.

One year, the National Film Board loaned a sound projector to the

mission school, and the settlement looked forward to an exciting winter

schedule of movies. Alas, after one or two showings of a program of

educational films - duly censored by the priest, who was operating

the equipment - the sound system failed, and the anticipated entertainment

ceased for the rest of the winter. As an example of the above-mentioned

censorship, when the male skater of a pair of ice skaters placed a

supporting arm around his female partner, a hand was hastily placed

over the projector lens to hide this shocking scene!

Both the HBC and RCMP posts possessed small and valued libraries,

and I was lucky enough to be allowed to borrow from them. We mostly

relied on receiving books, magazines, and papers whenever the mail

plane arrived.

Jill

admires the annual inspection turnout, August 1949:

Joe Funfer, Dick Watts, Hank Hoiland, and Bill Aird (the cook)

Annual

Inspection

Visitors from outside also provided entertainment. Their reception

sometimes required quite extensive preparation, such as for the army

inspection team that arrived once a year from HQ in Edmonton. This

ceremonial visitation meant that everything on the station had to

be in apple-pie order, including the boys. For the occasion, besides

polishing cap badges and pressing uniforms, they reluctantly replaced

their comfortable Native-made moccasins with polished army footwear.

Arriving at or about the same time as the Signals inspection team

were the medical and dental teams. This ensured a complete spring-cleaning

each year, not only for the station, but for its personnel too.

Summer

inspection, August 1950: Bob McKenzie,

Bev Berry, Curly Folkins, Al Miller, Dick Watts, and Bert Rupple

After

coping with the needs of the station staff and dependents, the medical

and dental teams would treat any inhabitants of the settlement who

needed their help. The dentist's travelling equipment included a sergeant

who pedalled away on the machine powering the drill, while the patient

sat in a small portable chair. To have a tooth filled or pulled in

this milieu was a daunting experience, but one much appreciated if

desperately needed. Seven months pregnant, I bulged over the edges

of the chair as the dentist offered an interesting observation. The

roots of the back tooth he was pulling were hooked exactly like the

teeth of Eskimos he had treated in the Arctic, and was thus very difficult

to extract. At least this ethnological titbit gave me something to

think about during the procedure!

Other visitors of interest included the famous Inspector Larsen, who

had made the first successful west-to-east voyage through the Northwest

Passage in the RCMP's St. Roch. When we were invited to meet him at

the RCMP quarters, I was impressed by how much he enjoyed talking

to my small children. He encouraged little Chris to page through a

book from the Mounties' library, while the constables, understandably,

looked a little worried about the damage a small boy might inflict

on its pristine condition.

The renowned bush pilot Max Ward was another famous visitor, and we

entertained him to supper. Anyone who has travelled on Wardair, which

he founded later, cannot help but wish that it were still in existence,

providing the most comfortable flights ever.

Lost

in the Bush

When Ken Hunt, the manager of the HBC post, went hunting one Saturday

morning, his wife expected him back with a couple of prairie chickens

for supper. But time went by, and by nightfall he had not returned.

It was fall, and the weather was beginning to get cold. Poor Peggy

Hunt was really worried. I went down the road to the HBC post to stay

with Peggy and her little girl, Lynne, while everyone from the settlement

who was able went out to look for him.

The Sigs station had a searchlight whose beam was used for estimating

the height of the cloud ceiling. It was turned on in the hope that,

if Ken had become lost, he might see it shining up into the sky and

thus be able to find his way back to the settlement. But there was

no sign of him.

The following day everyone again went out looking for him, again with

no success. Just towards dusk, Ken reappeared at the outskirts of

the settlement, to the relief and joy of the searchers. It turned

out that, although an experienced northerner, he had indeed become

lost. This is fairly easy to do in that featureless expanse of the

bush.

In order to orient himself, Ken had climbed a tree, and he had indeed

seen the searchlight's beam. He had lit a fire and spent the night

in the bush before making his way home, very tired and dirty. The

whole settlement, as well as his family, was delighted to see him

return safe and sound.

Yellowknife

While looking through some old papers recently, I found a memorable

bill from the Red Cross Hospital in Yellowknife. It was dated December

14, 1949, and asked me to settle my account, as they had failed to

charge me for the October portion of my stay there. The total bill

for seven days, October 30 to November 5, was $84.00. And more than

worth every penny of it, too, as the medical expenses were for the

birth of our second child, Christopher, on October 30.

In the more isolated parts of the North, delivering a baby was more

complicated than it was outside. The army would have paid for my trip

to Edmonton, but I knew no one there, so I preferred to stay closer

to home. This meant chartering a plane to and from Yellowknife, arranging

somewhere to stay, and estimating how long I would spend there. Gillian's

arrival was three weeks late, but I must have improved with practice,

as Christopher, bless his heart, arrived exactly when I expected him.

Getting to Yellowknife was the first stage of the expedition. On the

day the chartered plane was supposed to arrive to pick me up, the

weather was so poor that we expected it to come on the following day.

However, it arrived as planned, and I, alas, had eaten a hearty lunch.

As the river was just beginning to freeze up, it was impossible for

the Norseman floatplane to edge right up to the riverbank at the RCMP

compound. The efficient Mounties kindly pushed me out to the plane

in a small boat. I awkwardly clambered up into the plane to sit behind

the pilot. He greeted me with, "If I'd known you were pregnant,

I wouldn't have come today."

Getting

on the plane to Yellowknife

We

took off, and soon that familiar queasy feeling came over me. I asked

the pilot if he happened to have a vomit bag in the plane. He answered

that he had none, but if I looked behind me I would find a loaf wrapped

in waxed paper, and I could use the bread wrapper. I thanked him and

used it gratefully, much relieved - in more ways than one.

As we flew on, the short day began to draw in, the sky clouded over,

snow began to fall, and a strong headwind started to blow against

us, making progress difficult for the plane. The pilot seemed anxious

and asked me a couple of times if I could see anything, but all I

could see were snowflakes falling on the grey lake below. I wondered

if we would have to set down before we reached Yellowknife. I didn't

really care if we did, so long as we landed somewhere.

At last we caught a glimpse of Yellowknife across the grey water.

We landed at a deserted dock at five o'clock, fifteen minutes after

our expected time of arrival, with the needle on the gas gauge nearly

at "empty." The pilot commented that it had been a rough

trip, and helped me out of the plane. He showed me a small building

from where I could phone for a taxi.

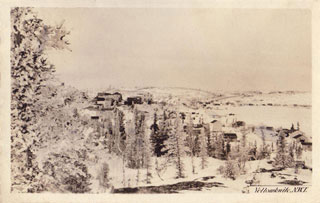

Yellowknife:

The building in the background is the

liquor store, in the centre the RC Signals Station and

in the front the RCMP detachment.

There

was, very fortunately for me, an NWT&Y Sigs station in Yellowknife.

The WO in charge, George Batty, and his wife had very kindly offered

to put me up for a week or so before and after the birth of the baby

at the hospital. Before I could even use the telephone at the dock,

kind Mrs. Batty, warned of the plane's arrival, drove up in a taxi

to take me home with her. The Battys made me very welcome, and their

adorable little girl, Carol Lynne, reminded me of Jill.

Yellowknife

(Post Card)

A

pleasant few days ensued as I enjoyed such metropolitan delights as

daily walks with Mrs. Batty to the coffee shop of the Ingraham Hotel

on the main street, for refreshment and conversation with any friends

who turned up. We also went to a cinema a couple of times, and this

was a great treat.

We visited the local school, just across the road from the PMQ, to

see their Hallowe'en parade. That evening, my labour pains began.

Accompanied by Mrs. Batty, I adjourned to the hospital at eight o'clock

the next morning, a Sunday.

Hospital

The nurse who greeted me at the hospital said that she hoped I would

hurry up and have the baby soon, because the doctor was anxious to

go hunting. I did my best to oblige and things progressed in the usual

way. In the delivery room the doctor told the nurse to give me some

chloroform for the pain, cheerfully informing me, "They don't

believe in using this in England." I vaguely remembered that

Queen Victoria had had chloroform during childbirth when it was a

brilliant new procedure, but I could not help thinking that there

had probably been more recent advances in anaesthesia. However, since

the Queen survived and produced umpteen more children, it seemed likely

that all would be well.

The assisting nurse seemed unsure of how to administer the chloroform,

but the procedure was successful, even if it was in the Victorian

mode. Christopher turned out to be a beautiful, healthy boy and was

as good as gold. The doctor seemed quite pleased at the end with everyone's

behaviour, including mine and the baby's. I discovered later that

the regular doctor was on leave outside, and my doctor's usual patients

were workers in the Yellowknife goldmines!

It was rather dull in the recovery ward, as I was the only one there.

My only visitors were the two parish priests, one Roman Catholic and

one Protestant, carrying out their pastoral duties. The RC priest

was worried that the Russians would invade Canada through the NWT.

I reassured him that such a thing was not at all likely. Having seen

what an effort it took to start our station truck and water pump and

to keep them going in winter temperatures, I couldn't see an army

of tanks and trucks from Russia managing to cut through thousands

of miles of bush from the Arctic coast to Yellowknife. It felt quite

safe to state categorically that it was impossible.

After a week in hospital and a further week's stay with the Battys,

I felt strong enough to charter another plane for the trip back. This

time the pilot was the well-known bush pilot Ernie Boffa, who was

as pleasant and thoughtful as he was efficient.

Some fresh food was available in Yellowknife because of its much more

frequent plane service than ours. It seemed sensible to take back

as much as I could, so, carefully fulfilling the requests from Fort

Providence, I ordered as much as I could, including some Christmas

turkeys. By this time in November the lake and river were frozen over,

and the planes were on skis for the winter. It was difficult to get

the heavily loaded Piper Cub off the ice, and two men had to rock

the wings to free the skis. As we zoomed up into the air, one of the

turkeys fell from where it was stowed somewhere above me, luckily

missing the baby.

The day had started with fine weather, but by the time we were halfway

across the lake it was grey and overcast again. Ernie said that he

might have to put down but didn't think that this would be a good

idea because of the baby. He thought it wiser to return to Yellowknife,

so we turned around and went all the way back. It was a tremendous

disappointment.

Next day we set off again, and this time we made it to Fort Providence

and landed on the airstrip. Ernie settled the baby and me in one of

the H-huts while we waited for the truck. When it arrived, he immediately

presented Dick with a bill for the flight - even before he got to

see his new son. We forgave Ernie though, as we knew he was anxious

to get back to Yellowknife before dark

It was wonderful to be back home. When we arrived, Jill was down the

road with the Schoales, happily playing with their little girls. After

we had settled Chris in his crib, Dick went to get her and introduce

her new brother. She was thrilled to see him and looked forward to

having someone to play with all the time.

The new baby's first photo: Dick, Chris, Veryl Schoales,

and Jill, November 1949

The

Sigs boys were pleased, too. Apparently the whole settlement had known

I was pregnant practically before I knew myself, and they had been

betting on the sex of the infant. The Signals staff had, fortunately,

all bet that it would be a boy!

The news of Chris's birth had arrived in Fort Providence by radio,

and the operator on duty had rushed over to our house to give the

proud father the news. He found Dick inside the big water tank in

the basement, cleaning it out. This incident was included in the station's

monthly report in the system's publication, Notes of Interest, and

was immortalized by the clever cartoonist who illustrated every Notes,

giving its readers much amusement.

Off

the Air

Two weeks after my return to Fort Providence with the new baby, we

went through a very disheartening experience. The engines, which enabled

the station generators to supply power to light and heat the station

and the quarters, ceased operating one after another - just when the

weather was starting to get uncomfortably cold. It was November, and

the high temperature that month was 50ºF (10ºC) and the

low -20ºF (-29ºC). In December, while the troubles continued,

the high was 39ºF (-4ºC) and the low was -50ºF (-45.5ºC).

Dick discovered our situation when he woke in the middle of the night,

switched on the lamp over our bed, and no light resulted. The regular,

comfortable putt-putt of the engines was missing - nothing was to

be heard except the occasional howling of the dog teams tied up outside

the cabins. After the emergency equipment was used to send a message

to HQ explaining our predicament, silence perforce ensued. We were

off the air!

As our plane service was rather limited, obtaining replacements for

the defective engine parts by air was not the easiest thing in the

world. At this especially crucial time, the eagerly awaited parts

were bumped off the plane in favour of some passengers from Fort Simpson,

the Signals station south of Fort Providence. If we were not to freeze

for another month, a charter plane was needed to deliver the urgently

needed parts. HQ in Edmonton finally gave permission for this; their

main concern seemed to be that the weather reports were not coming

through. In the civilized environs of Edmonton, it was perhaps not

immediately obvious what lack of power meant for those living on the

station.

I could not help but be concerned about my little girl and her baby

brother, who was only three weeks old. No electricity meant no lighting

except what was provided by candles and, later, a camping lantern

kindly loaned by the Hudson's Bay post. It meant no heat except from

that provided by the minuscule flame in the cookstove. We did have

an oil-fired space heater, but we had to put it in the basement room,

where our year's food was stored, so that the canned goods would not

freeze. Fortunately it was possible to shut off the kitchen and the

living room next to it from the rest of the house. With the aid of

the tiny flame in the cookstove, we were able to keep those two rooms

at a reasonable temperature, but the rest of the house was about 40ºF

(45ºC).

The RCMP constables came over to cheer me up and presumably to rescue

us if things deteriorated further. I believe that the problem was

eventually found to have been caused by the new engine bases that

were put down in the previous summer, which turned out to be not quite

level. It was an occasion for celebration when the repairs were finally

completed, the lights came on, and we could start the furnace again

and have life return to normal!

After this interlude, life continued according to our usual routine

until July 1951, when we received sad news of the death of Dick's

father and went on leave to Ottawa. The children were introduced to

the delights of "outside." On the way, they had a wonderful

time in the Macdonald Hotel in Edmonton, where the kind girl in charge

of the elevator let them ride up and down as many times as they wanted.

They also had fun flushing the toilets, over and over again.

On our return to Fort Providence we heard that we had missed the big

excitement. A big CPA plane, on its regular trip to Norman Wells,

had suffered engine trouble, and its twenty-five passengers had to

be put up overnight while repairs were made. Although we were sorry

to miss this event, it was convenient that our house was vacant and

its beds available - there weren't very many spare beds in the settlement.

The only trace of the passengers stay in our house was a cigarette

burn on a bedside table.

Life carried on in the usual way until July 1952. After four years

in Fort Providence, Dick was promoted, and it was time once again

to move, as is customary in army life. Our new destination was the

most northern station in the System, Aklavik, where Dick was slated

to take charge of the radio station.

[Next

Page]

Pages: [1] [2]

[3] [4]

[5] [6] [7]

[8] [9]

[10] [11]

[12] [13] [14]

[15] [16]

Return to top of

page

Return to the Watts

Family page