Page4: Ft. Providence (continued)

Tugboats

and barges bringing in supplies

Yearly Rations

All the bulkier supplies, including food, oil for heating, gas and

oil for the truck and the engines, and most of the bits and pieces

necessary for maintaining the equipment, arrived in the summer. These

vitally important items were transported on barges pushed by tugs

down the Mackenzie from Hay River. Goods first had to traverse a portage

to Hay River from Fort McMurray, the terminus of the railway system

on which everything had begun its journey from the South.

It was, of course,

imperative to ration these supplies to make them last over the whole

year, which objective sometimes needed some ingenuity to accomplish.

Each man was entitled to a year's supply of rations, for which $37.50

per month was deducted from his pay. The same amount was also deducted

as rent for our PMQ. An extra man's ration share could be ordered

for each "dependant," as wives and children of soldiers

were termed. We chose instead to arrange for a little variety in the

menu by ordering a year's supplies from Western Grocers, a wholesale

firm in Edmonton. Very careful ordering was essential and taking everyone's

preferences into consideration was a must. On returning to southern

life I found that buying groceries once a week seemed an unnecessary

and incredibly fussy way of doing things!

Meat came either

in cans or as frozen carcasses, which were hung in the refrigerator

unit and were jointed and shared out by the station cook. Milk was

powdered or canned, and fruit and vegetables came dried or in cans

or bottles. It took a very long time indeed to get the children to

eat fresh fruit and salads when we finally returned to southern Canada,

as they were so used to canned and frozen food. The concept of fresh

food was almost completely alien to them, although we did manage to

grow a few lettuces and did occasionally get some fresh fruit in by

air.

One could also

obtain sacks of potatoes and eggs, a crate at a time, but I cannot

remember how these were obtained or where they came from. I think

that the suppliers were fairly local and sent these items in by local

plane or boat. Bread, cakes, cookies, etc. were made from the flour

and baking supplies provided in the rations. I soon got used to baking

bread twice a week.

The Pelican Rapids, the Hudson's Bay Company

supply boat.

When the river

became free of ice in June, the boats that had been laid up for the

winter were able to run again and resume bringing in supplies. Before

then, if one had been unable to make the year's rations stretch over

the winter, it was sometimes possible - at very high northern rates

- to buy the missing items from the Hudson's Bay post or from the

one local native trading post. But the added cost of importing supplies

to the North made this a very expensive proposition. Any supplies

that were desperately needed could be sent by air (and received if

weather and landing conditions were favourable), but again this was

a very expensive procedure.

Since I had experienced food rationing in England during the war,

this way of life posed no problems for me and I never ran out of supplies.

It did take me some time, though, to understand the warning from Jorgy

not to give the station cook any vanilla essence if he tried to borrow

some after running out of his yearly supply. To my surprise, I discovered

that this alcohol-based flavouring essence was regarded as a standard

alcoholic drink. I remember one Easter the "boys" expressing

their hearty thanks when I sent over some hot cross buns. They said

they particularly enjoyed the vanilla icing!

Dealing with

Diapers

One of the several challenges to be faced was baby laundry, and perhaps

only the parents of babies are able to appreciate the ramifications

involved. This was, of course, before disposable diapers. Things have

changed so much since those days that I feel an explanation of baby

care then is necessary for a modern audience. Diapers were in those

days made from cotton cloth cut and hemmed into a shape that was almost,

but not quite square. One folded the diaper into a shape suitable

for either a boy or a girl (the thick side either fore or aft), and

then pinned it with two large diaper safety pins, one to each side,

to the baby's little undershirt.

A recent improvement

had made available paper diaper-liners, which, even if expensive,

did save some of the labour involved. They could be discarded after

being soiled, leaving the diaper only slightly dirty. These liners

also washed quite well if one accidentally included them in the laundry!

Used cloth diapers

were rinsed in the toilet and then placed in a covered diaper pail

filled with water to which a little disinfectant had been added. At

the end of twenty-four hours, there would be about a dozen soiled

diapers in the pail, and each day these had to be washed.

If one's baby

developed diaper rash or if the diapers began to lose their pristine

whiteness, one had to boil them on the stove in a large container

of soapy water, rinse them in fresh water, and then dry them on the

clothesline outside (if the weather was warm enough). The washing

process of course necessitated a supply of water and a means of heating

it, which, although a matter of course for those living "outside,"

was not quite so easy in the North.

In the winter,

it was wonderful having a large basement in which to suspend clotheslines.

Here I could hang the washing to dry after it had been washed, rinsed,

and put through the wringers of the washing machine. This practice

was common in many houses, including army PMQs, in other parts of

Canada.

I developed a

great respect for the Slavey mothers, whose babies were always spotlessly

clothed, even if the older children were a little on the grubby side.

Their clotheslines, like mine, always bore a long line of diapers!

And of course, subsequently, training pants! Those mothers were seldom

lucky enough to have husbands who carried water or ice from the river

for them, as mine did for me when it was impossible to pump water

from the river. Their husbands were usually away on their trap lines

in the winter and perhaps too busy fishing in the summer.

Native Inhabitants

The medical authorities in the south had warned us not to let our

children play with the native children because of the prevalence of

tuberculosis in the North. This was a terrible scourge among native

families; sufferers were obliged to spend months and even years away

from home in special TB hospitals. Consequently, when one had small

children, it was impossible to do more than just pass the time of

day with any of the natives. I was never able to know any of them

well.

The Slavey women

were adept at making wonderful moccasins, mukluks, mitts, parkas with

fur-trimmed hoods, and other articles out of the tanned skins of various

wild animals. They embroidered the articles beautifully, using designs

apparently based on the wild roses that grew everywhere and whose

fragrance in the long, warm days of summer permeated the air.

They were especially

expert in moose-hair tufting, a craft that I believe is unique to

Fort Providence. The moose hair was stitched in tufts to the material

to be ornamented and then trimmed to produce a very pretty mossy effect.

These craftswomen were so skilled that, if you put in an order for

moccasins or mukluks, they needed only one swift glance to estimate

the size of your feet.

I once made an

embroidered flannelette baby jacket for an expectant mother. She responded

later, when I was expecting my second child, with an exquisite pair

of baby moccasins in bleached caribou skin trimmed with white rabbit

fur and embroidered beautifully with a charming moose-hair tufted

pattern. The moose hair was dyed in the traditional pink and green,

which colours made the rose design a very convenient one. Alas, my

family all have enormous feet and the little moccasins were too small

even for the newborn baby. On the other hand, this enabled me to keep

them as a precious souvenir for years!

The Slavey men

were all expert trappers, hunters, and fishers. In the summer they

would catch large quantities of fish in the river. The fish would

then be dried and smoked on wooden racks set up either in front of

their cabins or on the river edge. These fish would be used in the

winter to feed the dog teams.

Having previously

only read about the Native way of life in tales of adventure, I expected

to find these North American Indians paddling the canoes from which

they fished. It was a big surprise to find that although they did

use paddles, their main means of locomotion for a canoe was a small

outboard motor, or "kicker"!

Jill on front gate, with dog team passing

along the road

Dog Teams

A familiar sound throughout the year was the melodious howling of

the sled dogs. When not hitched up a sled, the dogs were chained each

to its own doghouse outside the Native dwellings. From these doghouses

the chorus of howls travelled through the village from team to team,

to be finally taken up by wolves outside the settlement. At night

it was a wonderful, eerie, northern sound.

Dog team with sled and driver

At times the "boys"

at the station would run a dog team or two. Inexpert drivers sometimes

confused the commands for right and left. When the team turned sharply

from the compound gate to the main road, the driver would be leaning

the wrong way, and was completely unbalanced. He would end up in the

snow with the sled on its side, its load upset and the dogs all excited

and tangled up in their traces. This was not much fun, except for

the spectators, especially when the load was the station garbage on

its way to the dump!

All the dogs

loved to run, and the drivers' long whips seemed to be used only for

cracking on either side of the team to encourage them and occasionally

flicking the ear of a misbehaving animal. To encourage the dogs to

run faster, drivers made a soft trilling noise like the Scottish rolled

R.

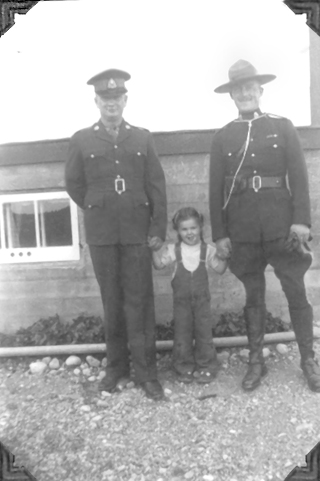

Constables Norm Hambley and Tommy Scott,

RCMP,

and Jill. Note the lettuces growing in the background.

One of our two

RCMP constables, Tommy Scott, a novice in the North and on his first

patrol with the dogs, had a difficult time controlling his team at

first. It was the start of winter, but all the water in the creeks

was not yet frozen. The excited team kept tipping the sled over in

water, getting all tangled up in their traces and fighting with each

other. The poor man had to take his mitts off to untangle the traces,

his hands began to freeze, he could no longer feel what his fingers

were doing, the dogs were still fighting, and he was at a loss as

to what to do next. Then, in desperation, he had an incredibly bright

idea: he bit the ear of the lead dog! It worked instantaneously -

he was now the master of the team. The lead dog quieted down and behaved

himself from then on.

Tommy was a little

tougher with the team from then on and did not let them get so out

of hand. He had left Scotland only eighteen months before and thought

of dogs as pets rather than working animals. (Another memory of Tommy

is of him trying to teach my children to say "Och aye!"

instead of "yes" and "Och noo!" instead of "no."

It never actually caught on, in spite of his best endeavours.)

The RCMP dogs

were particularly tough, as they were part wolf and bigger and heavier

than the malamutes used by most families. When Dick was introduced

to them in their fenced enclosure at the Mountie compound, one dog

stood on its hind legs and put its forepaws on Dick's shoulders, its

jaws wide open, panting hotly into his face. Dick in those days was

six feet, two inches! It was quite a terrifying experience and he

was considerably relieved when Constable Norm Hambley assured him

that the dog hadn't seen too many people lately and was just making

friends!

[Next

Page]

Pages: [1]

[2] [3]

[4] [5] [6]

[7] [8]

[9] [10]

[11] [12]

[13] [14]

[15] [16]

Return to top of

page

Return to the Watts

Family page