Page 1: Fort Providence, NWT

Introduction

Living in the North in the late nineteen-forties and early fifties

was a fascinating experience - one that I have always greatly valued

and never regretted, although at times it was neither easy nor pleasant.

For my husband, Dick Watts, and me the original lure of the North

was a financial one. An extra $100 a month in isolation pay would

make a substantial contribution towards the future purchase of a house

of our own. We decided to make the plunge and asked HQ in Ottawa for

a transfer. During the required interview with a psychologist, Dick

was somewhat surprised when asked if he and his wife liked to play

games. What sort of games was not specified, but the question made

for some interesting speculation for us!

Getting There

I am writing this in the year 2002; it is now fifty-four

years since that day in the summer of 1948 when I went to the airline

office in the Chateau Laurier Hotel in Ottawa to book a flight to

Fort Providence. It was somewhat surprising when the young woman behind

the desk told me that the airline didn't fly there. However, after

I pointed out the settlement's location on the map behind her, she

revised her first response. I was able to book two seats - for my

baby daughter Gillian and myself - for the flight north.

Perhaps it is no wonder that Fort Providence's existence

did not immediately spring to the airline clerk's mind. It is a very

tiny settlement indeed. A close look at the map will locate it in

the Northwest Territories, on the north bank of the Mackenzie River,

almost at the beginning of that river's long journey from Great Slave

Lake to the distant Arctic Ocean.

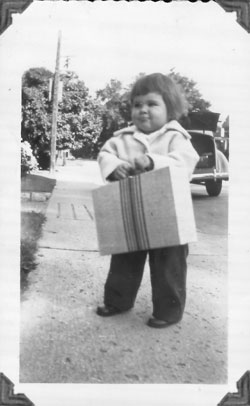

Jill and her travelling case of toys

Our journey took place in mid-September 1948, Dick

having already arrived at Fort Providence at the beginning of the

month. The first stage, in a Trans-Canada Airlines Dakota, took us

to Edmonton, where in those days the Macdonald Hotel was the tallest

building in town. Little Jill, fifteen months old, was full of energy

during the long flight. Her small attaché case of toys was

not absorbing enough to keep her occupied for the entire trip. I was

very grateful when the kind man next to me, obviously a father himself,

offered to hold her for a while. During the flight he pointed out

to me how the colour of the soil changed to a darker hue when we flew

over Manitoba; I remember being much impressed with this phenomenon.

After deplaning at Edmonton we arrived at last at

the Macdonald Hotel, exhausted after the long flight. It was a something

of a shock when the receptionist, refusing to believe that I had made

a reservation, stated that the hotel was full. My father-in-law, an

old soldier himself, had advised me to get a letter of confirmation

of our reservation - his advice proved to be a very good idea indeed.

On production of this undeniable proof we were finally admitted, and

went to bed in peace and comfort for the night.

Very early next morning, we took a taxi from the

hotel to the Edmonton airport and boarded the Canadian Pacific Airlines

plane, a Dakota DC-3, for the long haul north. After flying 1500 miles

over nothing but an enormous quantity of bush, with an occasional

isolated little settlement in its midst, we finally arrived at the

Fort Providence airstrip. We were now farther away from Ottawa than

Ottawa was from London. As a war bride from England I felt this to

be a most impressive display of the incredible vastness of Canada.

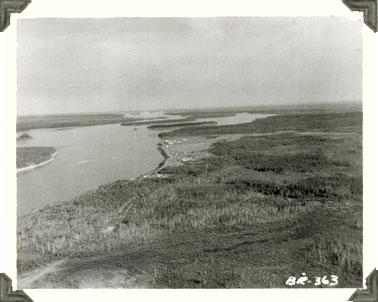

Fort Providence airstrip

Arrival

The only buildings to be seen on the bush-encircled airstrip were

empty H-huts left over from its wartime construction by U.S. troops.

The "boys" at the wireless station had apparently been quite

sure I would be horror-struck at the sheer emptiness of this arrival

spot. Actually, it reminded me of my childhood in the Australian bush,

where my family had lived for two or three years in the twenties,

so its lonely deserted aspect had a rather familiar feeling for me

- I failed to be shocked.

Dick was a very welcome sight. He had driven in the

station truck the three miles from the settlement, and was waiting

to meet us at the airstrip. The truck, a half-ton Dodge "Beep,"

was one of only two motor vehicles in the tiny settlement; the other

belonged to the Hudson's Bay post. Traffic on the few roads consisted

of pedestrians and sleds pulled by dog teams, so there was not very

much traffic duty for the local RCMP.

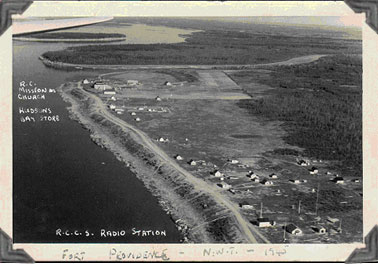

Fort Providence (Zhahti Koe: "Mission House")

When Alexander Mackenzie stayed at Fort Providence

in the eighteenth century, some Yellowknifes, a Chipewyan people,

were living there. The present settlement was founded by South Slaveys

of the Dene nation, not long after the Roman Catholic Church established

a mission school there in 1896. The Hudson's Bay Company established

a fur trading post at about the same time. The usual northern joke

about the Hudson's Bay Company's initials standing for "Here

Before Christ" was not very apt here; this time Church arrived

before Commerce! During our time there we noticed that the Natives'

surnames were mostly French and Scottish, which presumably reflected

their families' historic connections to the fur traders, voyageurs,

and missionaries.

When I arrived in the tiny settlement, Fort Providence

lay in a narrow strip along the north bank of the Mackenzie River.

From the airstrip we drove along the main road, which ran through

the bush, parallel to the river, to Fort Providence. First we passed

the RCMP compound on the left, and then, after more bush and two or

three Native cabins, we reached the Signals station compound with

its 96-foot-high radio masts. Beyond this welcome sight were, facing

the river on the right-hand side of the road, more houses, the Hudson's

Bay Company trading post buildings, the Roman Catholic Mission church,

the Mission boarding school, and the Oblate Fathers' buildings. The

road finally ended at the docking area, where the river tugs deposited

the loads from their barges and the occasional small plane landed

on the snye (channel) beyond.

The broad Mackenzie River, along whose northern bank

the settlement lay, was of enormous importance in our lives. Originally

the only means of transportation in that part of the Northwest Territories

- apart from dogsleds - it was the principal route for supplies from

the South. When one looks at an atlas, one instinctively looks up

the page to find north, so one thinks "up north" must be

the logical expression. However, the sight of this impressive mass

of water flowing rapidly downriver to its Arctic Ocean outlet instantly

convinces one that the local usage, "down North," is more

appropriate!

At Fort Providence the river was both pure and fast-running.

It provided us with excellent water for drinking and for washing ourselves,

our clothes, and our homes, as well as for watering our small crops.

Fish from the river fed both people and dogs. In the summer, one could

even swim in its waters whenever - very occasionally - the temperature

reached a respectable level!

The fall freeze-up of the river was complete by the

end of October. In our hamlet, as in many places in Canada, a good

many bets were placed on the date the ice would break up in May. Spring

break-up began somewhat grudgingly at first and then proceeded with

noise and commotion and days of miniature icebergs floating downriver

from Great Slave Lake. Ice was still floating by on my birthday in

early June.

[Next

Page]

Pages: [1] [2]

[3] [4]

[5] [6]

[7] [8]

[9] [10]

[11] [12]

[13] [14]

[15] [16]

Return to top of

page

Return to the Watts

Family page