The Royal Canadian Corps of Signals In The North: How

It All Began.

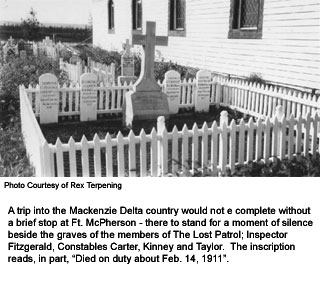

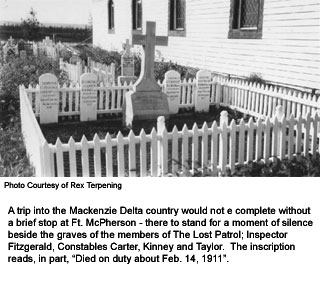

In

the early days of the fur trade industry in the North, news and messages

were almost entirely verbal affairs, carried from trading posts to

cabins, and cabins to camps, by word-of-mouth-and often transferred

from individual to individual enroute. And as the travellers were,

for most part, mocassin-clad, then this informal message relay system

became known as the "mocassin telegraph". Where urgency

was not a factor, this served admirably - ack of alternates was also

a consideration, of course. The need for something more efficient

became apparent, however, when the early aircraft made their first

exploratory flights into the north during the 1920s.

The

Imperial Oil Co. flights of 1921, with the present-day Norman Wells

as a goal, were the first airborne venture "north of 60°.

Their misadventures were well-publicized as was the extreme isolation

of the entire NWT during the winter months. Many people in other parts

of Canada were realizing, for the first time, that vast areas of our

Dominion were completely out-of-touch with civilization for much of

the year.

During the period of the Twenties (and for a couple of centuries prior

to that) the north was fur trade country - nothing else mattered.

Surface communications were provided by the boats of the Hudson's

Bay Co. in summer and by the occasional dog team in winter. Law &

order was the responsibility of the RCMP, from widely scattered posts

across the north. The only other Federal Government representatives

were doctors, four in number, provided because of treaty agreements

with the native bands. Sovereignty was also a factor. The earlier

presence of the American whaling fleet, based at Herschel Island,

was a long-standing concern of Ottawa's. Herschel was presumed to

be in Canadian territory but we had only a lone (and usually out-of-touch)

RCMP Detachment to enforce our claim. Communications between Ottawa

and their representatives in the north were confined to the brief,

open-water period of the summer.

Partially

as a result of the publicity generated by the IOL flights, plus their

own obvious needs, the Federal Government then took action. A chain

of radio transmitting/receiving stations was planned, to link Edmonton

with the small settlements along the length of the Mackenzie River

System. But this was the mid-Twenties- radio transmission by voice

was in its infancy. The electronics needed for the transmission of

text and morse-coded messages were less demanding, however, both as

to cost and power requirements. Such equipment had been developed

for commercial applications and was readily available. The program

started in 1924 with the construction of stations at Edmonton, Ft.

Smith (the then capital of the NWT) and Ft. Simpson. The following

year saw the addition of Aklavik, thus completing the year-round communications

link between Government Administrative Offices in Edmonton and their

counterparts in the north. Problems were experienced however in reliably

bridging the roughly 800 mile gap between Aklavik and Ft. Simpson.

An additional relay station was needed-Ft. Norman was then added in

August, 1930.

Air exploration of the NWT by mining companies began in the summer

of 1927, to be followed by commercial flying down the Mackenzie the

following year. Winter flying began in 1929-the first winter airmail

flight left McMurray on January 27 with mail for Ft. Simpson and intermediate

points. Problems soon appeared, however, emphasizing the need for

better communications. On Jan.29 this same aircraft suffered structural

damage while landing at Ft. Resolution. Repairs and assistance were

needed from Edmonton but the nearest radio station was at Ft. Smith,

far to the south. The mocassin telegraph then came to the rescue-in

the form of a man on snowshoes. I'll quote now from other sources:

Word of the plane's mishap had to be sent out. The nearest wireless

was at Ft. Smith, some 180 miles away through bush, muskeg and untravelled

wilderness. Jim Balsillie, a young northerner, took the message, travelling

through heavy snows in temperatures of 40 degrees below zero. He travelled

the 180 miles in 50 hours-a record that will forever stand. The reply

came that night over Edmonton's CJCA radio broadcast: "Relief

plane enroute Thursday (signed) Western Canada Airways."

This was at a time when few aircraft existed-many Canadians had yet

to see this new form of travel. The drama of a damaged aircraft, somewhere

in the wilds of the north, and a rescue message delivered by snowshoe,

made headlines across Canada. That Government awareness of this need

was influenced by the publicity there can be little doubt. Approval

quickly came for another station - at Ft. Resolution.

The existence of the Signals Stations, at trading posts throughout

the NWT, had a considerable, and favourable, effect upon the everyday

life of the residents of those frontier settlements. The Operators

at the Stations provided a daily (though unofficial) news link with

the Outside. The physical needs of the stations (water, fuel plus

a measure of casual labour) added a few precious dollars to the meagre

local economies. And the local craft-ladies did a thriving business

in richly-ornamented mukluks & moccasins, mitts & parkas.

Most of all, though, the Operators, at all stations, became very much

a part of the local population. They became involved in whatever small-scale

social activities existed - making life more bearable, and enjoyable,

for the others who shared their lonely life.

Early

aviation service in the north, and particularly for those of us who

provided it, received substantial assistance from the Signals operators.

This was of particular importance during the long, dark months of

winter when so many of our flights operated under the most difficult

of winter conditions. The official duties of the operators consisted

only of the transmission of commercial messages, but the duties they

performed went far beyond that. They provided an unofficial safety-net

for our day-to-day operations. Our early aircraft were not equipped

with 2-way radio facilities but, though lacking these contacts, the

Signals boys made it their personal business to keep track of our

movements. They passed along the word, from station to station, of

our planned destinations, our enroute stops at smaller posts or trappers

cabins, and the approximate arrival time at our destination. It was

always comforting to know that an alert would quickly be sounded if

our aircraft failed to arrive - if we were forced down due to weather

or mechanical problems.

I

can well-remember a typical incident that took place in the winter

of 1937. We were southbound from Ft. Norman, caught in bad weather

and forced-landed, off-course and far to the east of Ft. Simpson.

We had our tent and emergency rations. Oerations such as this were

not uncommon in the Thirties. We did carry tiny, battery-operated

radio transmitter/receivers, for emergency use. During the evening

I strung-up an antenna and switched on the set. Using a hand-key I

sent a brief message on our fixed-frequency, advising of our location

& situation. I repeated this several times, hoping that some station

might hear our tiny, weak signal. I did not expect a reply as the

RCCS transmitters were on long-wave, far above our frequency. Much

to my surprise I received a reply from Simpson. They acknowledged

our message, advised of their weather conditions - and they would

pass the word of our situation along to the other stations. We reached

Simpson in the morning without incident, gassed-up and proceeded southbound.

I never did determine the source of the Ft. Simpson transmission,

and I have since learned that the transmitters in use in 1937 might

have been tune-able to our frequency. There is also the possibility

that the Simpson operators might have constructed a "ham"

transmitter, crystal-controlled, to our frequency.

In

retrospect our situation was far from ideal. We were a considerable

distance off the "beaten-path" - that being the Mackenzie

River. Our fuel supply was marginal. If the weather was "down"-and

we burned extra fuel by "wandering"... well, the "wandering"

might become walking. I

will never forget the warm feelings that message exchange gave me

- that the Simpson boys would spend the evening, glued to their set,

wondering and worrying about us. And I have no doubt that this situation

was repeated at Ft. Norman and Ft. Resolution - that operators at

those stations were also listening on our frequency, on the off-chance

that our weak signal might be picked up. And as a final (and most

important) comment: hotels were few & far between in those early

days in the north. We were always welcome guests at any of the Signals

Stations.

I'll

speak now of Aklavik. Because of its key location-adjacent to the

Arctic Coast and near the mouth of the great Mackenzie River, the

trading post of Aklavik was of key importance, both for transportation

and for communications. A considerable number of traders and trappers,

both white and native, populated the vast delta of the Mackenzie.

This included the posts at Ft. McPherson, farther upstream on the

Peel River, and Arctic Red River Post, south on the Mackenzie. The

tiny settlements at Herschel Island, and Tuktoyaktuk on the near Arctic

Coast, were also dependant upon Aklavik for support, summer and winter.

Aklavik

was important as the distribution point for all cargo along the Arctic

Coast by boat in summer. There was only a single winter exchange of

first-class mail along the coast each winter. These were carried out

by members of the RCMP Detachments, with the Cambridge Bay detachment

making the round-trip one year and Aklavik performing the duty the

following year. Battery-operated radio receivers were then on the

market and the Signals staff at Aklavik constructed and operated a

small broadcasting station. This provided a news and message service

to the trading posts, to RCMP detachments, to the boats in summer,

and to isolated posts along the coast of the Western Arctic, summer

& winter. The life of the residents of the Mackenzie Delta was

immeasurably brightened, and often made safer, by the presence and

actions of the RCCS staff at Aklavik.

Because

of it's prominence as the largest settlement in the western Canadian

Arctic, Aklavik attracted a number of notable visitors. Celebrities

such as such the Lindbergs stopped by during the flight that provided

the material for Anne Lindberg's book, North to the Orient.

The famous duo of Wiley Post, of round-the-world flying fame, and

the well-loved American humorist, Will Rogers, spent a few days at

Aklavik. Though none would have realized it, their farewells at Aklavik

were final. They were killed in a crash later on the day of their

departure. The search for the Russian Trans-Polar flier, Levanevsky,

was centered at Aklavik for part of one summer and all of the following

winter. One of our Governor-Generals, Lord Tweedsmuir, also included

Aklavik in his schedule. With little in the way of hotel accommodation

at Aklavik, the Signals Station also played host to some of those

illustrious visitors. This function was unplanned but greatly appreciated,

both by the recipients and the hosts. A few photos are included to

serve as a partial, though typical, record of the life of the Signals

operators at Aklavik in the Thirties. These have been posted in this

website under the Aklavik Station heading.

For

the records I should add a few words concerning my own past experiences

- to validate, as it were, some of the statements that I have made.

My folks were Hudson's Bay people and I grew up in the Ft. McMurray

area. After learning the craft of an aircraft mechanic (Air Engineer

Licence # 1106) I was then employed by Canadian Airways Ltd. Working

from our operational base at Ft. McMurray we provided service to all

of the trading posts in the NWT and the Western Arctic, winter and

summer. I had many interesting experiences during those several years

and still retain warm memories of the Signals operators we knew. They

were always concerned for our safety and welfare - ever ready to lend

a helping hand. Wish we could go back and do it all over again, chaps!

With

kindest regards,

Rex

Terpening

rev.09/01/03