Peter Sinclair (page2) ---

Tales

from the Territories : Wrigley Station

By Peter Sinclair

The original camp at Wrigley

was built as part of the Canol Project by the U.S. Army's Construction Battalion

which was comprised mostly of black soldiers. In order to service the project,

a series of airstrips were built at Ft. Smith, Ft. Providence, Ft. Simpson,

Wrigley and Norman Wells - all about 175 miles apart. The original camp was

at a small river two or three miles north on the MacKenzie River. It was called

Camp 8-Ball. The Airstrip is on a high level bench area above the river bank

which, at this point, is about 250-300 feet high. I am not sure when R.C.

Sigs were first involved but Dick Bullock was there in 1946 when it closed.

That is why he was sent in as NCO i/c in 1948 when it was reopened. The station

was reactivated because the Department of Transport's metrological bureau

needed more weather coverage. The stations at Reliance, Brochet and Ennadai

were opened at the same time.

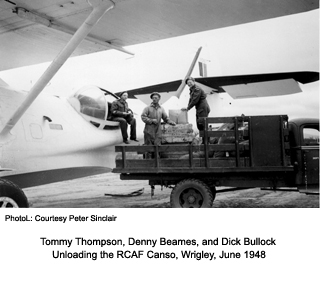

The reopening of Wrigley R.C. Sigs Station. To staff the station Hal Zinn came down river by boat from Ft. Simpson with Beams and McQueen (our Service Corps cook). Dick Bullock and I arrived by Canso aircraft from Calder with WO II Thompson, who was sent in as the System's representative for the handover from the Department of Transport (DOT). The DOT rep came in from Ft. Simpson to locate the inventory, some of which were missing - mostly tool kits. Of the metrological inventory (the barometer and thermometers, etc.) only the barograph was left.

|

One

thing we quickly learned when winter came was that shaving was a no-no.

Normal temperatures are -25 to -35 degrees Fahrenheit. Sitting high up

on an open Cat, in those temperatures on a windswept airstrip, where you

could not use a parks hood because it interfered with keeping an eye on

the rollers and drags behind you was a quick trip to frostbite. We were

getting frozen patches on our faces and found that one lap of the 4,000

odd feet of airstrip, a circuit that took about 25 minutes, was all we

could do. We would put the D7 in neutral and walk back in to the shelter

with another operator taking over and so on until the airstrip was serviceable.

At one point in the winter of '48/'49 the temperature was below -40 F for

several weeks without let-up. |

|||

|

We worked seven days a week - days, evenings and midnight shifts - with a short drop on the shift change. At the end of each shift the last duty was to fill eight oil stoves, each one using five gallons of diesel fuel that had been warmed near a stove then refilled from a fuel dump. Cold fuel would not flow through the stove filters. Really cold diesel oil looks like milky ice crystals and is very thick. Alongside

the normal met. and radio duties the station required a lot of "housekeeping".

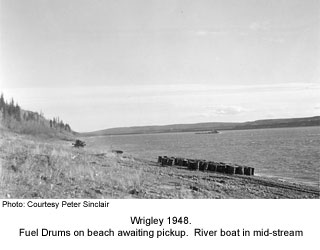

All supplies were landed on the riverbank about a mile away.

Rations, POL, building materials, etc., were loaded on stoneboats and hauled uphill and into camp. Rebuilding the stoneboats seemed a never-ending task. |

|

||

|

Heavy loads such as fuel drums (10x45 gal. drums = 2 tons) ground down the logs quickly. Nothing could be left on the beach for long as you never knew what the river would do. |

|||

|

When

the snow came, dragging and rolling the airstrip became a major task. Calder

recognized the workload and allocated an additional operator. Cpl Joe Murree

came in from Ft. Churchill late November. The extra pair of hands made

life a lot easier.

The

Water Supply. It must have been mid-December when we were ahead enough

water to half fill the washing machine. Hal Zinn was running the washer

with each of us having a little pile equal to ½ load. Joe Murree

had only been on the station a few weeks and watched with apprehension

as the washing water passed grey and was well on the way to black, with

Hal insisting it was good for a couple more loads. The truth was we didn't

even have rinsing water.

Water

was not a problem as long as the beach road was open. One trip a week to

the spring with 8-10 barrels was usually enough. The spring came out of

a gravel bank, was channelled between the bank and the road. Then under

the roadway to a spur road where the water was loaded. the problem came

during freeze-up when the spring water overflowed the road, freezing on

an angle that made it impossible to use the road. that was when we had to

melt snow. Water barrels filled with snow were packed around the Coleman

oil stove in the kitchen. As the snow melted it was decanted and refilled

with fresh snow - preferably crystallized snow from underneath that had

a better water content. The cook had first call on the water with a little

left over for a face wash. Bathing was restricted to a cat wash. Landing

supplies. In the normal daily routine of running the radio station

the operator on the evening shift did camp chores during the day, assisted

by the "mids" operator until lunch. During the open-water transportation

season, if a boat came in it was "all hands" at work until the

stores were off the beach and safe in camp. The river could be quite unpredictable

in its rise and fall, so stores were never safe on the beach.

To

illustrate that point, the first boat downriver in 1949 was the Yukon

Transport Company boat MV Sandy Jane, carrying building supplies for two

of our station/quarters buildings, warehouses, etc. Lumber, bricks, cement,

wallboard, furnaces and tanks, electrical and plumbing equipment, etc.,

were all dumped on the beach along with two 100 ft. antenna masts.

At that point our beach road was still out, with a huge ice flow jammed diagonally through it. We at first tried using the bulldozer to move the ice, but because of the angle the dozer blade deflected upward, so it was axes against a 7-foot thick barricade of ice. Then

the river rose!!!

There was no way we were going to move this mountain of supplies before it floated off or was destroyed. Panic messages went off to System Headquarters in Edmonton (Calder) for authority to hire local labour to rescue our supplies. Calder said OK, but at a rate of 90 cents per hour. The local rates were $1.00 an hour. Leo Kotowich, the local Hudson's Bay Company factor said "no problem". He was the one who was going to hire and pay the local help and then bill DND. Leo said to work them nine hours and pay them for 10. We had a dozen workers appear with Leo and we billeted and fed them for three days, almost round-the-clock, to move the stores with the water steadily rising. Steel mast sections, bricks, etc, were left to go under water, but everything else was saved. When

all this happened Scotty McQueen said he was not going to feed a gang

of Indians - and quit. Cpl. Dick Bullock, the NCO i/c sent Scotty back

to Ft. Wrigley with Leo, and I was nominated as cook. This was the second

time I had been drafted into this chore, the first time being when McQueen

got his feet frozen the previous winter.

A few weeks later Howie Crowell and Ken Stewart came in to oversee the erection of the 100 Ft. LF antenna masts. At this point half the steel antenna sections were still under water. There was nothing for it but to strip off and swim to find them. Some were easy - chest deep where you could feel for them with your feet, duck down and hook in a meat hook, then haul ashore with a rope. The ones in deeper water were harder to find, groping around in opaque water, icy cold with a 5-mph current. The ice had only been gone for a couple of weeks. Everything was found except for one centre splice (2 ft. x 2 ft. x 3 ft.) which didn't show up until the water went down. Eventually we got our masts up. Passtimes. We had a small library left behind by the Yanks. Some books dated from the 1890s! Our subscriptions were to magazines such as Readers Digest, Argosy and Aeroplane. Aeroplane had plans to build flying models which took us back to our teen years. An order to an Edmonton craft store brought in a large box of balsa wood, glue, dope, etc. and we were in business. This was a good way to pass the dark time. When weather permitted, the models were flown on the airstrip. One of the more successful models was a "Cygnet" that survived many crashes. We lost a sailplane on the second flight when it kept on climbing and was gone. |

|||

Return to Top of Page

Return

to People page

Back to other Peter Sinclair Pages [1] [2]

[3] [4] [5]

[6] [7] [8]

[9]

Go to Stories page